The Gospel With Flair. Spend Yourselves. Be Different.

Downlands Oration 1990,

by Bishop E.

James Cuskelly MSC

Ladies and gentlemen - Good evening.

Some years ago I paid a visit to the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Indonesia. In Amboina, half an hour after my arrival, somebody shot the

presbytery dog. This was done (so they informed me) because the dog was

large and meaty and would make an excellent dish for a festive celebration

about to take place. Next evening, I was invited to a festive meal. Spread

around the table were several platters containing different kinds of meat. I

asked one of the Indonesian priests: "Is there any dog on the table?". He

examined everything very carefully and said "No. No dog." I enjoyed the

meal; but on the following day I told my priest friend that I had an upset

stomach. "Oh", he said, "that, no doubt, is caused by the rat you ate last

night"!

Indonesia. In Amboina, half an hour after my arrival, somebody shot the

presbytery dog. This was done (so they informed me) because the dog was

large and meaty and would make an excellent dish for a festive celebration

about to take place. Next evening, I was invited to a festive meal. Spread

around the table were several platters containing different kinds of meat. I

asked one of the Indonesian priests: "Is there any dog on the table?". He

examined everything very carefully and said "No. No dog." I enjoyed the

meal; but on the following day I told my priest friend that I had an upset

stomach. "Oh", he said, "that, no doubt, is caused by the rat you ate last

night"!

Whenever the question you ask is limited, the answer you receive can prove

to be inadequate. Tonight I am attempting to give an answer to a question,

or a request, addressed to me. I hope that I will manage to give an adequate

response, and that you will suffer no unpleasant aftertaste.

I need hardly say that I feel truly honoured to have been invited to give

this initial "Oration". I should like to thank those who invited me. I

congratulate them on their choice, not their choice of a speaker, but their

choice of a title for the speech. It does have a ring about it. "The Gospel

with flair. Spend yourselves. Be different." The Committee came up with the

title. That was the easy bit. I had to come up with the talk.

In preparing the oration and in deciding on the title, we were agreed that

in beginning a new tradition, we should go back to the wellsprings from

which we drank in our College days. I should try to conjure up something of

the special spirit which the MSC priests and brothers brought into our lives

when we were young. As memories stirred among the Committee members, they

thought of John Doyle's favourite exhortation: "Be different'. They recalled

the total dedication of the priests and brothers who "spent themselves" in

the apostolate of education. Their generous fidelity came from the Gospel

as, too, should come our call to be ourselves in our unique personal

dignity, daring to differ whenever Christian principle demands it, whenever

the Gospel calls us to do so. Someone stated his conviction that different

though many MSC had been from one another, they had one thing in common:

they did things with style: The Gospel with flair.

It has been my good fortune to have known many Missionaries of the Sacred

Heart across the world and to have seen them in action. You people have met

the Tylers, the Bells and the Codys. I have met our picturesque people in

more than thirty nations. In their widely differing ways of spending

themselves, there has indeed been flair, and always, at times heroically,

they have lived the Gospel.

Just now I mentioned Fr. Cody. You knew him as a mild and gentle man. But,

in his own way, he, too was different. He was a New Zealander. He

disapproved of violence and war, and in order to avoid having to serve in

the New Zealand army, he came to Australia where he lived the rest of his

life in exile. For 21 years, from 1931 to 1951, he taught at Downlands. Many

of you knew him but did you know that, outside, flying through the

Australian night there is a moth named after him. As a seminarian, George

Cody had a pen-friend called Gustaf Hulstaert. Gustaf, an MSC student in

Belgium, had a special interest in the study of moths. Among the specimens

sent him by George Cody was one that, as yet, had no scientific name. In

honour of his pen-friend, he called it "sideridis codyi" (Of the Noctuidae

family). Let me remind you, for reasons that will be obvious later, that the

Oxford dictionary defines a moth as "an insect resembling a butterfly that

usually flies by night."

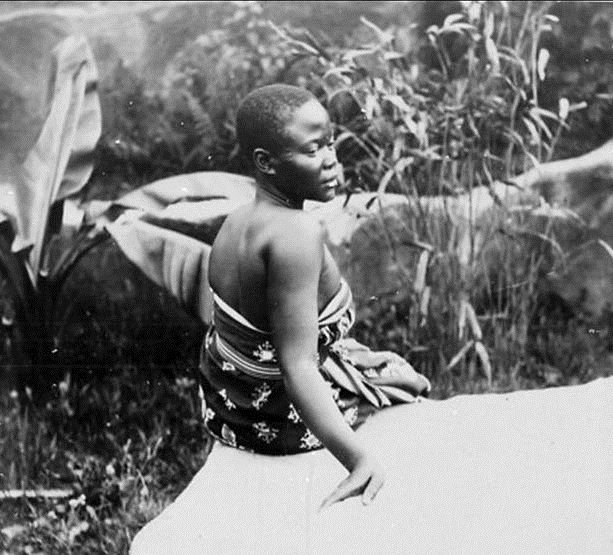

I met Fr. Hulstaert in Africa in 1971. As a young

priest, he had gone as a missionary to the Belgian Congo. There, like Adam

in the Garden of Eden, he gave names to all around him - to other moths, to

butterflies, to trees and flowers. He noted the songs of the birds; he

listened to the people as they sang. He wrote down their ballads and their

stories. He became an expert in their language and their folklore. He was

the one who supervised their translation of the bible. Altogether he

published book-shelves full of works on the flora, fauna and folklore of

Zaire, the old Belgian Congo. Let me quote just a few of their titles: 'The

Mongo People and Witchcraft", 'The Bafoto language", "Ancient and Modern

Mongo poems", 'The dialects of Bakutu", "The use of medicinal plants among

the Mongo people", "The roots of Baum Philosophy". Certainly for me and

possibly for you, these works would hardly make for bedside reading, but

they show the wide range of his scientific mind. More than Stanley ever did,

Gustaf Hulstaert discovered the Congo, its life, its spirit, its own special

character. When last I heard, there was talk of erecting a statue to his

memory, even though Stanley's statue has disappeared long since. The people

knew who it was that helped them to discover themselves.

I should like to relate an incident which illustrates a different aspect of

Gustaf's missionary life. Once as he and I were talking, there was a power

failure and we were plunged into darkness. Gustaf said: 'Thanks be to God".

I commented: "Not many people thank God when the lights go out." "Not many

have the same reason, as I do", he said - and he explained his reasons to

me. In the early 1960s there had been an attempted revolution in Zaire.

After some initial successes, the revolutionaries were defeated by white

mercenaries. In revenge, as they made their way homewards, they decided to

wipe out any whites they met. They stopped at the Mission station of Boende,

threatened the missionaries with their guns and bound their hands. A brother

was allowed to start the generator for the lights of the mission station.

When the MSC were told that they were to be shot, they asked for time to say

a prayer. They knelt, and the lights went out. The natives were astounded -

this was surely a sign that God was displeased with them. Terrified, they

fled into the night. What had happened was less dramatic than they supposed.

From the fuel supply to the engine which operated the generator, there was a

long pipe with a tap at either end, one at the tank, the other at the

engine. In his nervousness, the brother had forgotten to turn on one of the

taps, the tap from the tank. The engine started because it was fuelled by

the small amount contained in the connecting pipe. When this supply ran out,

the engine stopped, the lights went out, the Africans fled, and a number of

lives were saved - and ever since, some people give thanks to God when the

lights go out.

I pass now from the jungles of Africa to one of the most sophisticated

cities of the world. In Paris, the Place Pigalle is a well-known place.

Tourists see it as a place of neon-lights and the Moulin Rouge. Locals know

it as the King's Cross of Paris. I think of it, and so do the French MSC, as

the field in which Fr. Jean Rosi worked for 45 years in an apostolate to the

prostitutes of Paris. And, my friends, thereby hangs a tale the like of

which you will seldom hear.

In his early years of priesthood, Fr. Rosi was like a French Fr. Cody. He

taught maths and science in an MSC College, only to boys. At the age of 40,

he was appointed to a parish in the suburbs of Paris. Once, on a parish

picnic out in the fields, one of the parishioners took an obvious liking to

him. She was a pretty young lass of seventeen. Like a butterfly she flitted

around the flowers of the field. She brought a posy to give to Fr. Rosi, and

told him that, like the girl in Les Miserables, she, too was called Cosette.

Some weeks later, Cosette informed him that, although she might resemble a

butterfly of the fields, in reality she was a moth who flew by night,

attracted by the neon lights of Place Pigalle. She was a prostitute, so were

her two sisters, and her other, as well. For Fr. Rosi this was considerably

different from his previous experience of a "boys only" world; he came down

to earth with a thud.

Those were the days of World War II, and the Germans had occupied Paris. One

night, Fr. Rosi was hurrying home from a sick-call, when, suddenly, the

lights of the city went out. For him this meant danger, not deliverance as

it had meant for his MSC colleagues in Africa. For, the Germans had imposed

a curfew on the city; anyone caught in the streets after curfew ran a grave

danger of being shot. In the dark, the door of a house was quickly opened

and a voice called: "Father, come in here." That night he took refuge in the

house of Cosette's family.

Those were also the days when the Cardinal Archbishop of Paris was

organising a sort of missionary drive among the workers and the

underprivileged of the city. Fr. Rosi was invited to join the Cardinal's

team and to suggest his own special field of work. Understandably, he felt

that he was called to work somehow for the prostitutes of Paris. But his MSC

Superiors had not a little difficulty in understanding what he was on about.

"What! Going to meet prostitutes every night of the week? Sundays included!

For spiritual reasons? What will people think if they know that the Rev. Fr.

Jean Rosi, MSC, is out there in the Place Pigalle night after night - and we

tell them that it is for the love of the Lord?" Poor Fr. Rosi was given an

ultimatum - either give up the call-girls or live outside the Society. One

night he found himself alone in the streets of Paris, his religious house

closed to him, not knowing where to go. Eventually he found accommodation

with an elderly benefactor.

You may wonder: how does one go about the specialised apostolate of

converting

prostitutes? In the seminary we learned a lot of things: how to prepare a

sermon, how to hear confessions, how to baptise a baby. But there was never

a course on "how to convert a call-girl". Fr. Rosi had to write his own

do-it-yourself manual. He visited the Place Pigalle almost every night. He

hung around. The word spread that there was an unusual sort of priest out

there. Should anyone wish to get out of the trade and into something else,

he would help. He never put pressure on the girls to change their way of

life. Taking that decision usually meant a big cut in salary, which they

might later regret. He hung around; for 45 years he hung around, and over

the years girls came to him whenever they got to feeling the darkness of the

neon lights, the despair and loneliness of the city streets, whenever they

wanted to change their way of life.

converting

prostitutes? In the seminary we learned a lot of things: how to prepare a

sermon, how to hear confessions, how to baptise a baby. But there was never

a course on "how to convert a call-girl". Fr. Rosi had to write his own

do-it-yourself manual. He visited the Place Pigalle almost every night. He

hung around. The word spread that there was an unusual sort of priest out

there. Should anyone wish to get out of the trade and into something else,

he would help. He never put pressure on the girls to change their way of

life. Taking that decision usually meant a big cut in salary, which they

might later regret. He hung around; for 45 years he hung around, and over

the years girls came to him whenever they got to feeling the darkness of the

neon lights, the despair and loneliness of the city streets, whenever they

wanted to change their way of life.

Jean Rosi was a most interesting person to meet - a joyful man, with a bald

head, bright blue eyes and a wonderful sense of humour. At the same time he

had a serious and perceptive view of the world. 'The prostitute", he used to

say, "stands as a symbol of our society. She sells herself for money - and

we despise her. At times we despise her because she is a reproach to us, a

reproach to a society which will sell its soul for money, for pleasure". He

used to ask a rhetorical question: "Are there any values that our society -

or people in our society - will not prostitute for material gain?" Mr. Tony

Fitzgerald would have some interesting answers to that question.

Explaining his do-it-yourself method of dealing with prostitutes, Fr. Rosi

used to say: 'The only way for a prostitute to be redeemed is for her to

experience respect from others. Nobody – nobody, respects a prostitute. She

is despised by other women; she is despised by men, even by the men who use

her. But, deep down, she has a crying need to be respected. Most of all she

needs to know that she is respected by a man, by a man who will respect her

as a person, while not desiring her as an object."

For 45 years Fr. Rosi spent much of his time showing respect to the

prostitutes of Paris. In turn, he won their respect and their affection. In

French, the term "ton-ton" is a familiar form of "Uncle". Jean Rosi became

known as "ton-ton Rosi", shortened eventually to "Tonsi". For many years you

could go into the streets of Paris and ask about a man called "Tonsi".

Almost every second person to whom you spoke would know whom you meant. Over

the years he helped a number of girls to a more respectable - and happier -

way of life. He was not popular with the pimps - he was too much of a threat

to their trade. At least three times he was hit over the head and left

unconscious in the streets. But, as long as he had the physical strength to

do so, he kept going back. It was in the 86th and last year of his life,

that he made his last visit to the Place Pigalle.

The first time that Tonsi told me his story I was fascinated. I asked him

hundreds of questions. Finally I asked him: "What about Cosette, the first

girl who came to you, the one who started it all. What happened to her?"

"Ah, Cosette", he replied, "Today she is a very respectable grandmother in

the south of France. After she married she used to come to Paris once a year

to take me out to dinner. Once she said to me: 'Tonsi,Tonsi, you must give

up this dreadful way of life; it is not fitting for a priest'. And I said to

her: 'Ah my dear Cosette, have you forgotten who it was who got me into this

terrible life in the first place?"

More than forty years after his superiors had left him alone in the streets

of Paris outside his religious house, I had the privilege of welcoming him

to our central house in Rome. As his Superior General, I was delighted to

say: 'Tonsi, welcome home!' But that is another story.

Let me pass now from fairytale to tragedy, from Paris in Europe to Guatemala

in Central America, where many MSC have lived and worked and some have died

a violent death. Guatemala is a delight to the eye and the ear. The

place-names ring like bells run wild: Chichicastenango, Sacapoulas,

Chimaltenango. There, in the highlands, the air is clear as crystal, the

colours of the Indian costumes are as brilliant as birds of paradise, and

the sun sets in a glory that is as warm as the smile of God.

In January 1980, in this strikingly beautiful land, I met with a group of

MSC missionaries, my friends and brother priests. On the shores of Lake

Atitlan framed majestically by its three volcanoes, we talked of the coming

murder of at least three of their number. We knew that a brutal military

government had placed their names on its hit-list. In Australia, we find it

hard to imagine the brutality that exists as an everyday reality in other

lands. However, though hard for some to believe, it is easy to understand.

Those of you who have seen the film "Romero" would have some idea of the

situation in many Latin American countries.

The Spanish conquistadors invaded Guatemala in 1522. They had horses; they

had guns. The Indians had neither and were easily defeated. The Spaniards

took for themselves (and their descendants) all the more fertile lands. They

made their own laws about land-registration. Their descendants prospered.

Some of them became very rich with plantations of coffee, sugar, bananas and

other tropical fruits. The Indians were driven back into the hills. They

knew nothing about land-laws. Deprived of their former lands, they set up

their little farms on the hillsides. There they grew their corn and their

peppers. They ran a few cattle, pigs and chickens and eked out an existence

right on the poverty line. There was a way for them to earn a few extra

dollars and to clothe their families. They could go down to the coast to

work on the farms and plantations of the rich. There they earned less than a

dollar a day - about $5 a week (I'm speaking of the 1970s). Australians

would earn between three and four hundred dollars a week for the same work.

Most of their $5 a week would be paid back to the rich to buy food and

clothes. The rich land-owners owned most of the shops as well.

Some years ago, MSC missionaries came from Spain to work among the Indians

who had been Christians of sorts ever since the days of the conquistadors.

The missionaries ministered to their spiritual needs. They also taught them

better farming methods; they imported superior quality cattle, helped them

to form their own cooperatives and to set up their own shops. The

missionaries also talked about social justice and the concept of a just

wage.

The rich families felt threatened. If they had to pay just wages, if they

lost their cheap labour, they would lose a lot of their wealth. They paid

the military to force the Indians to work for them, to destroy their

cooperatives and even to shoot their leaders. The next step was for the

'big-wigs' in the military to decide that, if they were to do the dirty work

for the rich, they should have some share of the riches. The army took over

the government. Then retiring generals and colonels also took over tracts of

land where the Indians were living. Invoking the old land laws, they claimed

legal justification for this robbery. If the Indians resisted, they were

shot.

Then the missionaries spoke out. They were not political men, but they were

friends of the Indian people. They had the courage to insist that the human

dignity of the Indians should be respected, that they had basic human

rights: they had a right to a just wage; they had no obligation to work for

the rich plantation owners - they had a right to the lands which the

military officers were stealing from them. It was a crime to rape their

wives and daughters; it was a crime to shoot their young men.

This proclamation of the Gospel did not please the rich and powerful. The

rich resented losing cheap slave labour. The military resented losing a

chance to get rich at the expense of the Indians. All of them feared that

the priests would make public the atrocities which the soldiers were

committing with the backing of the rich.

During those days in January 1980, on the shores of Lake Atitlan, surrounded

by the beauties of God's creation, we MSC discussed the ugly deeds wrought

by evil men. All of us were afraid. Some were afraid that they would be the

ones to die; the rest of us feared that soon we would have to bury our dead.

We asked whether it would not be best for those on the hitlist to leave the

country while there was still time.

Someone said to me later: "There's an easy solution. You are their superior;

just order them to leave." Like many easy solutions, this was no solution at

all. I was sure that the missionaries would not feel bound by any such

order. They believed that it was their duty to stay with their people, in

spite of the danger to themselves. Furthermore there are two ways of

destroying a missionary. One way is to assassinate him while he is carrying

out his duties for his people. The other way is to have him appear to desert

both his duty and his people. The second is, in its own way, a type of

death, and, for the dedicated missionary, it is worse than the first. They

stayed with their people and I went my way.

matyrs guatemualaDuring the next few months I heard of the death of three of

our priests. Firstly we learned that José Maria Gran had been killed, and in

Barcelona I shared in his parents' grieving. Then Faustino Villanueva was

assassinated and later Juan Alonso. All three were the most pastoral and

least political of men. Eventually, the Bishop declared the Diocese closed

and ordered all priests and nuns to leave. It was then that the other MSC

also left. Later some went back underground; we believe that at least one of

them is dead.

You will wonder: But how can people get away with such injustice? They get

away with it, firstly, by being very careful about interviews permitted to

foreigners. Secondly, they have developed their own philosophy of "The

national security as the greatest good". In this philosophy anything is

justified if it protects "national security". All that is opposed to it is a

crime. It is sedition to criticise officials; it is a crime to oppose the

government. It is a crime to oppose the military even when they are stealing

your lands. This sort of philosophy justifies all kinds of violence

perpetrated by the government. And sadly, President Reagan and others

believed that all opposition to a government in power was leftist or

Marxist. Nobody asked: how did these people come to government? Do they

govern justly? In Latin America many governments came to power by violence;

and they govern by cruelty and greed. But - I am wandering from my central

theme.

Like all religious orders, we MSC have a book of Constitutions which

describes our ideals and our way of life. The second Vatican Council asked

all religious to examine their Constitutions and bring them up to date. The

old M.S.C. Constitutions contain the words:

"Following the example of Jesus, we will strive to lead others to God with

kindness and gentleness. Trusting in God's grace, we will be ready, if

necessary, to lay down our lives for them."

During the 1970s, there were some who thought that this was romantic stuff,

beautiful but unreal. It should be omitted, they said. But in 1981 when we

met in Rome to finalise the rewriting of our Constitutions, we thought of

Jose Maria, of Faustino and Juan Alonso. We listened to this letter from the

Church in Guatemala which read: "Your priests saw the Indians going hungry;

they witnessed the suffering of the peasant families. They brought the light

and strength of the Gospel to stop the enemies of God from spreading death

through our land. This was their crime: to preach to all people their right

to live with dignity." Then we took up our pens and we re-wrote with pride:

"We will be ready, if necessary, to lay down our lives for our people."

Guatemala will be forever a part of my life. The Indians still suffer in

that beautiful violent land. In spite of the sacrifices made, their world

has not been re-born. We who knew them will live with the memory of our

martyred brothers - especially when we hear songs like these: "Empty chairs

at empty tables where my friends will meet no more. My friends, my friends,

don't ask me what your sacrifice was for."

I shall move northwards now to the U.S.A. where I was invited once to

conduct a seminar on training students for the priesthood. As part of our

study I asked all present to describe, in one sentence, the kind of priest

they would like to see coming out of their seminaries. In giving an answer

to my own question I said: "priests who have a deep respect for every man,

woman and child with whom they come in contact." The word "respect" has a

strong meaning. It comes from the Latin respicere to look again. Every

person is worth a second look. No-one deserves to be passed over. As I look

around this room, I see a crowd, I see faces. But, if I look again, I see

persons, individual men and women each with his or her, own special worth.

One day it struck me that in inventing my own description of the ideal

priest, I had simply described the MSC whom I had known:

My missionary in Africa, Fr. Hulstaert, had looked on all of God's creation

with respect and wonder. He had shared with the world his respect for all

creatures and all cultures.

In Paris, Tonsi had shown me how wide respect for people can reach and how

redemptive it can be.

Both of them had said: what God made is wonderful, admire it, enjoy it; love

it and laugh with it.

My priests in Guatemala had shown me that respect can be heroic, generous

and self sacrificing.

As I recall my Downland's days, I remember that this respect was very much

part of the MSC attitude towards us and part of the viewpoint that they

wanted us to bring to the world. [A small indication of this was that they

did not use nicknames for the boys. Bill Graham did but, of course, Bill was

an exception - a magnificent maverick. Most nicknames were not based on

respect - and therefore the Fathers avoided their use.]

That, I believe was the central focus of the MSC world vision, respect for

all of God's creation with a special respect for every person. Therefore

they could exhort us to "be different", out of respect for our own unique

personalities, for our own individual God- given talents.

At times I wondered how well the MSC had succeeded in lighting a spark in

the minds and hearts of those whom they were sent to influence. When I first

asked myself this question, in 1975, I realised that in September of that

year we would be provided with an answer of sorts as Papua New Guinea became

an independent nation. You see, the MSC had been the first Catholic

Missionaries to set up a permanent mission in Papua New Guinea in 1882. In

the intervening years they had educated many and influenced many more of

those who would attempt to shape the destiny of their own nation. [Bishop]

John Doyle had worked there for several years. No doubt he would have told

them to be different from many of the whites whom they saw in their land.

Many missionaries worked there; many of them died there. If you walk through

the mission cemeteries at Vunapope and Yule Island, you will be struck by

the young age of most of those who lie there, victims of fever in their late

20s or early 30s'. They came from Europe before the modern anti-malarial

drugs. They came young and young, too young, they died. At the end of 1940,

Fr. Ted Harris left the Downlands staff and went to PNG to fulfill his

missionary dream. The Second World War was in progress and the Japanese

soldiers proved too strong for the Australian troops. Fr. Harris helped a

number of them escape to Australia. He gave them his mission boat to do

this, and helped them with food and medical supplies. As the last of them

were leaving they tried to persuade him to come with them. They said: "The

Japanese will kill you if you stay. If you come away with us, you can return

at the end of the war and take over where you left off". Fr. Harris replied

that he had thought matters over very carefully. Although he agreed that he

would probably be killed, like the missionaries in Guatemala he felt that it

was his duty as a missionary to stay with his people. "If I leave", he said,

"the natives will feel that the Church has deserted them in their hour of

need. I could never come back and preach the Gospel to them again." He

stayed. Some years later a group of soldiers presented us with a chalice

which bore the inscription: "In grateful memory of Fr. Ted Harris who gave

his life for his faith and for the survivors of the 2nd 22nd battalion."

In 1975 we would have some idea of what their sacrifice was for, for the

people of PNG would declare what kind of nation they wanted to be. Would

they revert to the old paganism? Would they opt for the new paganism of

greed and materialism that marks much of our modern world? As they prepared

to write their new Constitution we wondered. What would they write, these

speakers of pidgin, "Dispela em i wanpela naispela ples. Plenti pipal i kam:

ol i gutpela pipal na oi i gat bigpela save". What would they write?

They wrote one of the world's most beautiful Constitutions and one of the

wisest. They wrote:

"We see the darkness of neon lights. We see the despair and loneliness in

urban cities. We see true social security and human happiness being

diminished in the name of economic progress. We must not be afraid to

re-discover our art, our culture. For us the only authentic development is

integral human development. We take our stand on the dignity and worth of

each Papua New Guinean man, woman and child.."

They took their stand on the respect due to their people and their culture.

In the mission cemeteries, the young men could rest in peace. Of course, PNG

will have to contend with all the effects of original sin; it can have no

fairy-tale path to human happiness. But, at least it has laid a firm

foundation of sound principles. May the people of this young nation fare

well on the road they have taken.

In 1982 I came back to Queensland. Here I met, or met again, many Downland's

past students. I met your wives, and more recently your husbands. I have

seen some of you at work in your chosen professions. There you perform

competently and with style. I have met some of you at home with your own

families. I am convinced that your success, at home and in your work, has

been due in no small measure to the fact that, long ago you learned to

afford respect to all those who would come into your life. You have

integrated well into your lives that key-concept of the MSC philosophy.

There are exceptions of course, even among you. For, it seems to be part of

the political creed of this country that a politician should never show the

slightest shred of respect for a member of the opposition: "The honorable

member for Huehuetenango is beneath contempt." However, even here there may

be a saving grace. I am informed that when an ex-Downland's politician shows

contempt for his political adversary, he does so with flair!

Ladies and gentlemen, men and women of Downlands, I come to the end of this

inaugural "Oration". I have told you nothing new tonight. I have not tried

to do so. I have interpreted my brief as one of helping us all to drink anew

from the fountain that refreshed us when we were young. You, as well as I,

have to thank Downlands for shaping our vision of the world and of life in

it. I could have tried to give a philosophical analysis of that vision. Had

I done so, I fear that you would have fallen asleep in your seat. Instead, I

have tried to describe the vision at work in the world - a vision of human

dignity, of human worth, a vision of respect shown to all people in the

light of the Gospel. I have given some glimpses of the way in which that

vision shaped the lives of other men and touched the lives of many. All of

them were different; they spent themselves, and in their own way, each of

them had style. They loved what God had created, they enjoyed it. They took

all things with light heart and good humour. Therefore they could leave them

behind whenever the good of people demanded it. In one sense, these men were

your brothers, too. It was my privilege to have known them. I hope that

tonight it has been your pleasure to meet them. And as my heart was lifted

and my life enriched by knowing them, so may yours be, too. Ladies and

gentlemen, I thank you.

Courtesy Australian MSC Province